from the Sibylline Press Series: Sibyls on Motherhood

Mother’s Day is Silly, She Always Said

by Susannah Kennedy

Mother’s Day.

Growing up, we never celebrated.

“Mother’s Day is silly, just an excuse to sell candy and Hallmark cards,” my mother would say.

“Every day should be Mother’s Day,” she’d add.

Though she kept no evidence (she was not one of those mothers who kept drawings on the fridge door), I know I must have brought home little elementary school cards made carefully with school paste and colored paper and awkwardly drawn words. She must have leaned down and given a hug and said, “Awww, thank you sweetheart.” Did I sense the reticence? I must have.

I certainly understood her anti-capitalist point. But like so many points with my mother, including her choice for suicide at a still-fit 75, politics was a façade that obscured something else.

I grew up learning not to care about Mother’s Day. One less thing to think about. One more thing to scoff at when May’s saccharine sweet television ads ran. Kind of like seeing chocolate Santas stocked in the supermarket shelves the day after Halloween. Come on, people, it’s not even Thanksgiving yet! I loved my mother. She knew I loved her. I didn’t need to prove it.

And then I started traveling. I observed there indeed was nothing natural about Mother’s Day. Nothing spiritual. Nothing sacred. Perhaps it was a straight-up marketing ploy to make someone rich. In the Arab world, for example, where I spent much of my thought and energy in my 20s, I found out Mother’s Day was celebrated on March 21, the first day of spring.

Notice the distinctly American flavor of this commemorative stamp:

Begun in Egypt in the 1950s as a well-intentioned campaign to encourage social engagement on behalf of women, the Arab world’s Mother’s Day also became associated with gifts and flowers and promotional campaigns. Why not buy the mother in your family something special? I remember seeing the balloons and cards appearing in Cairo stores all of the sudden in March.

Here is a modern supermarket ad.

During my years in Germany, I discovered Mother’s Day taking on a whole different flavor. The Nazi government had indelibly tied the celebration of motherhood to promoting the “German master race” and the encouragement of mothers who could produce lots of German babies. In 1934, the third Sunday in May was declared Gedenk- und Ehrentag der deutschen Mütter (Day of Memorial and Honor for German Mothers).

Germany’s modern Muttertag was redefined in 1950 based not on a governmental decree but on a “gentlemen’s agreement” among German florist and business associations. In East Germany, Mother’s Day ceded to International Women’s Day. Today Germans celebrate Muttertag in the same way we do, but as with many symbols in post-war Germany, including sports events, stamps and flag-flying, they also carry a wrestling with Nazi history, a whiff of something else.

For many years, I paid no mind to all of this. My mother was probably right. There was no sense to this Mother’s Day thing.

What changed was when I became a mother myself. I noticed then that the cultural rituals that I had dismissed (even Christmas candles and wreaths) little by little became appealing. I saw how joyfully my friends presented flowers, how they looked forward to bringing out boxes of decorations every year. I heard them planning to go home to visit their mothers for Mother’s Day. This couldn’t all be bad.

When I began reading my mother’s diaries after her suicide, some of the pieces of these puzzles fell into place. There were her Mother’s Day words at their worst:

May 8, 1994. I heard Phyllis prepared lamb on Mother’s Day. What a door mat she is. No self-esteem = no respect.

And there were wistful Mother’s Days:

Mother’s Day – May 8, 2003. I wish I had not caused Mother such pain — my height was not my fault, but my marriage was.

Mother’s Day – 2010. Susannah never calls me on Mother’s Day.

That last entry makes me sad. She had been so adamant about dismissing Mother’s Day I had never thought she might want me to call her. How I wish she had been open to talking about such changes. I’m guessing now that her dismissal of the holiday had been hiding something painful and therefore meaningful.

As with her suicide, there was always a truth to what she proclaimed. Mother’s Day, especially in the United States, is very commercial. Just as growing older in this country is facing an inhumane geriatric system. But it does not mean that the other, softer, connecting strands of acknowledgement and sentiment can’t also be there.

Perhaps my mother’s dismissal of the holiday was a fear of allowing herself to be loved. She had one child, a child who loved her deeply, and yet to admit to wanting to be celebrated is admitting vulnerability and emotion. It is easier to pretend it doesn’t matter.

When I became a mother, I learned to be softer. I learned to ease into a baby’s breath, to become still, to listen. I learned to trust in motherhood and in myself. And I observed. I peeked around corners as other mothers delighted in home-made cards and a special picnic in the park. I heard stories about children who proudly brought Mama breakfast in bed, or set the table with special pictures and flowers, always flowers.

I learned. And when my children started giving me watercolor cards and painstakingly drawn I Love Yous, I breathed and smiled and savored every minute.

And now I cry at the overblown sentimental ads in May. Every single time. In a good way.

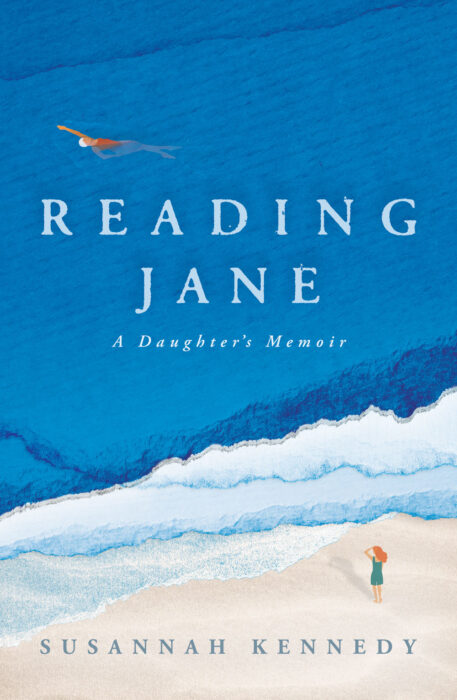

About Susannah Kennedy

Susannah Kennedy is the author of Reading Jane: A Daughter’s Memoir. A Berkeley and Oxford-educated anthropologist, Susannah Kennedy was born in India and raised in the United States. Later, she traveled extensively on her own, first in Italy, and then through the Middle East and India, settling for two years in Egypt before becoming a reporter in Dallas, Texas. At Oxford University, she specialized in Arab culture and politics, receiving her DPhil in social anthropology. She and her psychoanalyst husband lived and worked in Germany, raising three children in a thatched-roof farmhouse in the countryside outside Hamburg. Her mother’s suicide and its aftermath brought them back to Santa Cruz, California in 2017. They now reside in Marin County.

Susannah Kennedy is the author of Reading Jane: A Daughter’s Memoir published in September 2023 by Sibylline Press. Click here to purchase her book.

Susannah Kennedy is the author of Reading Jane: A Daughter’s Memoir published in September 2023 by Sibylline Press. Click here to purchase her book.