from the Series: Pride Month

Calling All Allies: The Battle against Book Bans

by Suzy Vitello

My 1970s childhood was marked by freedom, curiosity, second-hand smoke, and secrecy. Like many of my contemporaries straddling the Boomer-GenX line, I came of age during the Vietnam War, the fight for reproductive freedom, and, well, lots of confusion.

My parents flirted with counter-culture—when he wasn’t dressed in his Navy khakis, my physician father volunteered at a free clinic in San Diego. My mother, brandishing McGovern for President pins, dabbled in education before, on a whim, taking the LSATs, crushing them, and subsequently enrolling in law school.

Me, in the height of my awkward tween years standing behind my adorable sister. It’s no wonder I sought novels that centered weirdos.

Needless to say, my formative years were spent in unsupervised glee. My education (I attended public school during the era of pedagogical experimentation) was mostly self-directed, and I naturally gravitated toward contraband. Not booze or weed. We’re talking adult reading material.

I got a peek at the world of “grown-ups” by reading Jacqueline Susann and Sue Kaufman. While I found novels like Valley of the Dolls and Diary of a Mad Housewife curious, I couldn’t really relate to the women in those books. They were, for me, like the James Bond girls and the Playmates of the Month I read about in my father’s Playboys (messily stacked on the floor next to the family toilet): plastic.

Far more interesting were books like Harriet the Spy and Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret. And the frontrunner in the canon of adolescent angst, Catcher in the Rye. In other words, books about relatable kids and teens.

Like most tweens, my days revolved around wondering if I was normal. Wondering when I’d get my period and be chesty enough for a bra. I had weak eyes and crooked teeth and frizzy hair. A trifecta of despair. One of the few places I could receive solace and comfort was inside a story where the protagonist was an outlier. Where the heroine or hero lay bare their secrets and scars. It wasn’t just that I felt less alone reading these stories; I experienced something almost magical. A paradigm shift from freak to worthy.

As a mother of three in the 90s and aughts, I was a bit more hands-on than were my parents. When my middle child began to experiment with gender fluidity, I wondered what books or multi-media experiences were out there to help her feel less alone. Terms like non-binary and genderqueer weren’t yet part of the common lexicon—even in liberal Portland. Despite the popularity of Will and Grace (a sitcom I’ve always found pandering and inane), being a queer kid at the turn of the latest century was isolating. There was the whole “She’s a tomboy, she’ll outgrow it,” advice from some relatives, but when we moved to a new school district and she renamed herself in her quest to pass as a boy, my heart broke for what I knew was going to happen: Complete ostracization and cruelty from her peers.

Since stories (and horses, it must be said) had always been my remedy for dealing with exclusion, I looked around. Where were the queer books? Where were the queer heroes?

This endcap at Powell’s YA section would not be allowed in Idaho.

At the time, there weren’t many. But ten years later, things were finally looking up. According to best-selling, critically acclaimed author Malinda Lo, who’s been keeping track of the LGBTQ+ YA publishing/banning numbers for more than a decade, the early aughts and the subsequent decade saw a slow, steady rise in books centering non-cisgendered, queer characters. Since 2021, however, according to Lo, “[T]here has been an extremely disturbing surge in book bans in school districts and libraries in the United States. The most frequently targeted books are about people of color, LGBTQ+ people, racism, and history.”

Thankfully, my own queer child, now in her mid-thirties, is thriving, married to a wonderful woman, and is Mama to two fabulous boys. She holds a director-level job in a mental health organization, and, since she continues to reside in a welcoming, inclusive city, she isn’t confronted with the rampant homophobia that seems all too pervasive in much of the country—at least not in her day-to-day.

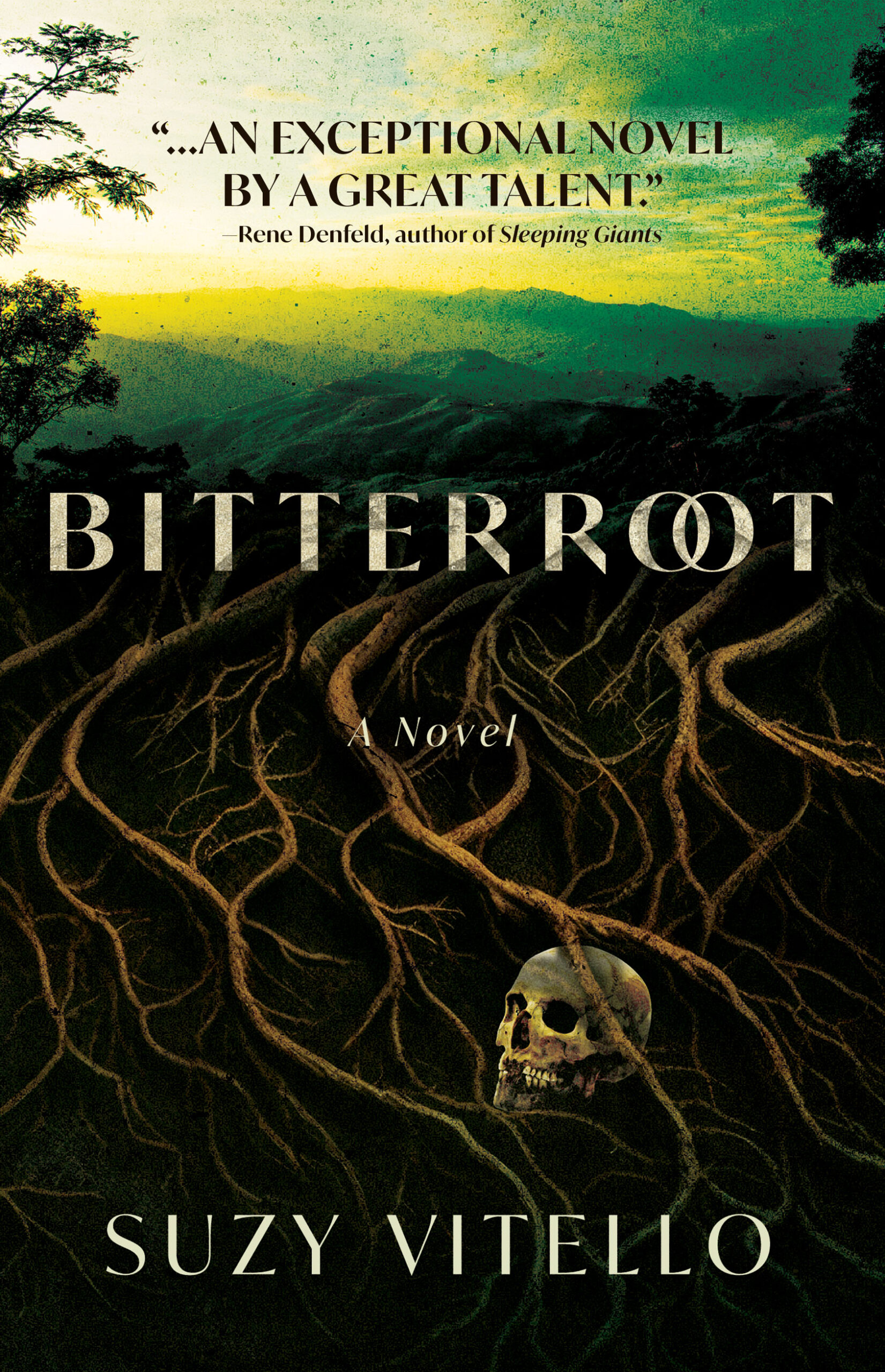

But we’re in a period of scary change, and the concern I have for growing anti-gay policies was one of the major drivers of my latest novel, Bitterroot, which is set in Idaho, and tackles the growing trend toward far-right policies. Right now, there is legislation being bandied about in that state that would force librarians to relocate books with “objectionable content” (their euphemism for anything touching on queer) to a restricted area open to adults only, thereby treating a book like Red, White and Royal Blue, for instance, as hardcore porn. An earlier bill (oddly numbered 666) threatened librarians and teachers with arrest should a minor come into contact with such a book while in a school or public library.

These draconian attempts to stymie adolescent curiosity and punish children who are seeking validation for their own normal, burgeoning sexual questions are part of a larger scheme to thwart critical thinking in favor of blind adherence to patriarchal subjugation. As readers and advocates for freedom of expression, we have the power to shape the future when we stand against book-banning in all its forms.

Pride Month is here, and it’s all-allies-on-deck to show support and be vocal about demanding legislation that protects gay rights, gay marriage, and stories that center gay characters. This year there’s even more at stake due to the election cycle. Should supporters of book-banning and exclusion have their way, queer kids, authors, and the reading public in general will find it harder to find books that represent a diverse array of characters, ideas, and experiences.

About Suzy Vitello

Suzy Vitello writes and lives in Portland, Oregon with her husband and her dog and occasionally one or more of their five kids. She holds an MFA from Antioch, Los Angeles, and has been a recipient of an Oregon Literary Arts grant. Her previous novels include Faultland, The Moment Before and the YA Empress Chronicles series.

Suzy Vitello is the author of Bitterroot: A Novel published in May 2024 by Sibylline Press. Click here to purchase her book.