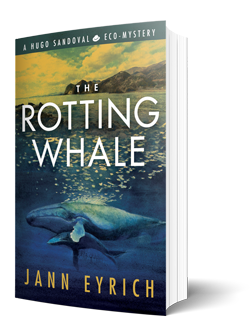

The Rotting Whale: Chapter 1

Excerpt from The Rotting Whale by Jann Eyrich

Hugo Sandoval, San Francisco’s quixotic native son, stared out his kitchen window for reassurance. It calmed him to watch the dawn grace the little white houses of the City below, its gentle whispers of light bleeding through the fog, creating shad- ows on the eastern face of Russian Hill that, to him, resembled craters on the moon. He suspected it was a quietude not often found in major cities.

While the building inspector waited for the dawn to take hold, his City yawned. Hugo was familiar with her stretches; they were soft, comforting, interrupted only by a cacophony of sounds from the waterfront below where streetcars glided on slick rails, street sweepers swooshed the gutters clean, and the occasional wildlife-car-alarm barked from the sea lion’s floating piers. Hugo called it City Radio, of which he was most definitely a fan, but that October morning, he was forced to tune it out. Something was gnawing at him; two somethings, in fact.

It had been a rough night for Hugo. It started with him drifting in and out of “the dream,” the one where he wanders a strange, hilly, even mountainous city searching for a road to take him to — well, he never knows where. Compelled to endlessly traverse a labyrinth of streets and highways, he always awoke before reaching his destination.

After he drifted back to sleep, the insistent house phone rang from its isolation in the living room to wake him like a slap. Hugo rolled over to look at the time on his cell phone. 4:14 a.m. The ringing stopped before he could throw back the bedding. No one calls on the house phone, he thought, fighting for a few more minutes of sleep, except—. Hugo’s cell phone started to buzz. He grabbed it in time, but the connection was weak and broke off. The phone buzzed again, and again failed to connect. The caller ID said A, A for Ava, his daughter. Since she had left the City for a remote marine research center up the coast, Ava was often out of range. Hugo was happy her career had taken off, but the distance had put a strain on the father-daughter relationship. The fact that she hadn’t called in weeks, and now, these pre-dawn attempts to connect left Hugo anxious and wide awake.

For the past sixteen months, Hugo had been the sole occupant of the top floor of an Italianate duplex perched at the north end of Grant Avenue. The spacious flat overlooking the waterfront was vintage San Francisco, but it was not his. Since his divorce Hugo had been house-sitting for an old friend, an esteemed professor emeritus at the Art Institute, Jean-Michele Moreau, JM. The professor had conveniently flown to Paris for an indefinite exile; an escape, he told friends. The night before his departure, JM and Hugo had trad- ed stories at Specs’ Bar where the artist confided more than a few truths over brandies. JM began with confessions of his own marital disasters before advising Hugo on his recent painful separation.

“Win her back, son,” advised the older Bohemian as he handed Hugo the keys to his flat. “Carmen is a rare work of art; formidable.” In his brief residency on the top floor of 2101 Grant Avenue, Hugo had pored through first editions of Howl and stacks of City Lights Journals; he listened with reverence to the rare, per- sonalized pressing of ‘Thelonious Alone In San Francisco’ on the flat’s vintage turntable. He wrote poetry at the kitchen table and, thanks to JM’s vintage candy-apple-red espresso machine, Hugo had renewed his love affair with the thick dark liquid. Although the scene had flared before his time, Hugo was content knowing that his own exile was framed in the art and artifacts of the Beat Generation, a culture that once defined his City.

It was a solemn Hugo who stood at the kitchen balcony sip- ping his double espresso with a clumsy mark of steamed milk that defined the macchiato; solemn and worried. He knew Ava’s work on the coast put her at risk from time to time—just last summer she and her team tracked a humpback whale entangled by fishing gear for two days until they were able to cut it free. He hated the risks she took, but he trusted her. His macchiato had gone cold.

Why was Ava trying to reach him at 4 am?

In the garden below, Mrs. Tsantis, the attractive proprietress of the North by South Greek Deli retrieved her Pomeranian from the rose bed. As was her nature, the neighborhood’s Greek siren casually allowed her dressing gown to slip off her shoulders. Hugo barely took notice that morning; instead, he closed his eyes and looked out over the Bay, inhaling deeply to drink in the tide on its retreat. The lingering breath of the Bay’s muddied shore remind- ed him he needed a shower. Before jumping in, he redialed his daughter’s cell phone, to no avail, and left another message with her office at the marine lab.

Hugo loved Jean-Michele’s shower with the floor-to-ceiling white subway tiles and the extravagant water pressure, which inspired some of his best thinking. It was a luxury, indeed an indulgence for a single man such as he. While his body longed to linger under the wa- terfall, he cut his shower short, but not before the hot water revealed what had triggered his recurring dream in the pre-dawn hours.

It was as he feared, the fallout that awaited him on Pier 50 was not the culprit; no, the trigger was far more intimate and disturbing, especially now with Ava in the mix.

Repeated texts had knocked Hugo’s cell phone to the floor.

Ping.

Their insistence bounced the inspector’s phone along the slip- pery linoleum out of reach. When he finally snagged it, wet feet squealing, he read, sorry dad. out of range. come see my whale. need you

He quickly texted back, where r u?

In the fall of 2011 Hugo was still a fan of the phone call. For him, the person-to-person touch was everything. Texts left him cold. What little he did know about texting he had learned from a teenage Ava on their explorations around the City. They were quite the team. He would show her where a decorative Victori- an cornice extended far over the next building’s façade, and she would demonstrate the art of texting while sharing a stack of banana pancakes at Mama’s on Washington Square.

Hugo stared at his hand hoping for any reply from his girl.

Nothing. No response to his text. He retreated to the bed- room to dress.

It was not unusual for Hugo to be called upon to resolve issues outside the normal routine of a building inspector. Colleagues re- spected his impassioned methodology and admired his calm, profes- sional demeanor as he sorted out puzzles of all shapes and sizes. In the course of his duties as a building inspector, Hugo might be found fac- ing off a slumlord or a corrupt politician, but he tackled more modest, more personal projects with the same dedication. These often yielded triumphs that seared him to the heart of the public. When the head- lines demanded comment, Hugo’s standard reply was, “It’s all part of the job.” At least his interpretation of the job.

What the public failed to see was how Hugo thrived on un- tangling the labyrinth of City regulations that had long hog-tied its citizens. That passion prompted his ex-wife Carmen to call the City Hugo’s mistress. As the years had unfolded, Hugo allowed his work to consume him, often pushing his marriage to the sidelines. What had been a good partnership fell apart.

Until the morning of the missed calls, Hugo had always been eager to take on new challenges, but this time it was different.

This time, it was attached to a face he loved. As he contemplated the steamed milk glued to the sides of his favorite mug, Hugo wondered if it was time to call the woman JM had branded as his formidable ex. But why alarm her with the facts? Even with his ego aside, he wasn’t sure Carmen was the call he needed to make.

While the early morning light forced its way through the leaded glass of the flat’s front door, he hesitated before going through. Perhaps it was to settle his Borsalino or straighten the crisp white cuffs of his shirt that had crept outside the sleeves of his trademark leather jacket, but whatever the reason, Hugo was caught off guard by his own reflection. In the glass of the hall tree, he saw the shadow of his father, had his father lived into his fifties.

“Tranquilo,” he whispered. It was time to call Harrison. Crossing the threshold, the worried father punched H on his speed dial.

* * *

Jann Eyrich is the author of a new eco-mystery series featuring building inspector Hugo Sandoval. When she heard about the stranding of a blue whale on the Mendocino Coast in 2009, the adventures of Hugo Sandoval were born.

Excerpted from Jann Eyrich’s new mystery book, The Rotting Whale: A Hugo Sandoval Eco-Mystery, available where great books are sold; Sibylline Press, ISBN: 978-1-7367954-3-9, Trade paper, 212 pages. $17.